Beyond the Gut: Exploring the Benefits of Butyrate

- Isabelle

- Jan 16

- 4 min read

As soon as the clock strikes 2 p.m., time seems to slow, my movements appear more sluggish, energy levels plummet, and all I want to do is go to sleep. To many people, especially other high school students around me, the usual afternoon crash or post-lunch drowsiness may seem typical. But, what if I told you that recent research has demonstrated the lack of a single molecule called butyrate may be responsible for these dips in energy, and increasing its production can lead to steady energy throughout the day.

Introducing Butyrate

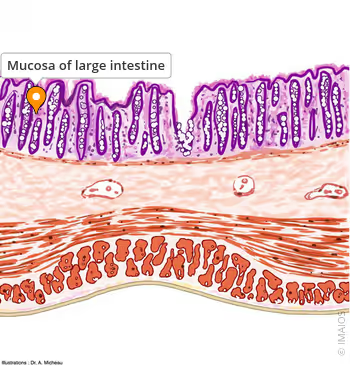

Butyrate is a short-chain fatty acid produced by microbes within our gut microbiome typically in our lower intestinal tract near our colon. In the colon, microbes metabolize soluble fibers and resistant starches that we eat and ferment them. During fermentation, the microbes convert acetyl-CoA into butyryl-CoA, which can then be transformed into butyrate (Esquivel-Elizondo et al., 2017).

How our Body Uses Butyrate

Since butyrate is produced in the lower intestinal tract, our colon cells can use the compound as energy. In fact, butyrate is the preferred energy source for colon cells, even over glucose. When colonic epithelial cells metabolize butyrate, they are able to produce mucin, a substance that lines the gut and is critical for intestinal defense. In addition to protecting the intestinal lining, butyrate also has anti-inflammatory effects that contribute to preventing colon-related diseases such as ulcerative colitis, chronic inflammation that is characterized by ulcers forming on the colon and rectum, and colorectal cancer (Esquivel-Elizondo et al., 2017), which is unfortunately increasing among younger adults (Masciadrelli, 2023). In the short term, butyrate can also increase insulin sensitivity, lowering glucose spikes after eating large meals (like lunch), and promote steadier, consistent energy throughout the day instead of crashes.

Negative Effects of Too Little Butyrate

If butyrate is lower in concentration, colonic cells have less fuel to work with, leading to less production of the intestinal mucus, and an increased risk of leaky gut, which can cause various undesirable symptoms such as bacterial toxins entering the bloodstream, inflammatory response like brain fog, fatigue and joint aches, food sensitivities, skin issues, and headaches (Leonid Kim MD, 2025).

How Can We Promote the Production of Butyrate

With all of the negative effects of not having enough butyrate, this poses the question of how we can generate sufficient amounts of butyrate to function optimally. As mentioned before, butyrate is produced by specific types of microbes—Firmicutes bacteria being a prime example (Kalkan et al., 2025)—which feed off of resistant starches and fiber, or carbohydrates consumed that remain undigested while passing through the small intestine into the large intestine. Ingesting food high in these dietary fibers can improve butyrate production. Some examples of foods high in resistant starches and fiber include berries, whole grains like oats and quinoa, beans, chickpeas, apples, sweet potatoes, broccoli, asparagus, and sweet potatoes (Leonid Kim MD, 2025). Additionally, omega-3 fatty acids have also correlated to promoting growth of butyrate-producing bacteria while suppressing the growth of harmful bacteria (Salsinha et al., 2025). To consume more omega-3 fatty acids, common sources include salmon and sardines while plant-based options include chia seeds, seaweed, and walnuts (Leonid Kim MD, 2025).

Key Takeaways

While researchers have yet to conduct further studies to demonstrate the efficacy of butyrate in randomized human trials, various studies have supported the essential role of butyrate in maintaining a healthy lower intestinal tract, which can impact a wide variety of bodily processes such as insulin selectivity in the short term to disease prevention long term. While butyrate is just one example of how important it is to nurture a healthy gut microbiome by consuming enough dietary fiber and resistant starch, learning more about how we can foster healthy diet habits can improve our daily lives, starting with one less 2 p.m., post-lunch energy crash.

References

Esquivel-Elizondo, S., Ilhan, Z. E., Garcia-Peña, E. I., & Krajmalnik-Brown, R. (2017). Insights into Butyrate Production in a Controlled Fermentation System via Gene Predictions. mSystems, 2(4), 10.1128/msystems.00051-17. https://doi.org/10.1128/msystems.00051-17

Grondin, J. A., Kwon, Y. H., Far, P. M., Haq, S., & Khan, W. I. (2020). Mucins in Intestinal Mucosal Defense and Inflammation: Learning From Clinical and Experimental Studies. Frontiers in Immunology, 11. https://doi.org/10.3389/fimmu.2020.02054

Kalkan, A. E., BinMowyna, M. N., Raposo, A., Ahmad, M. F., Ahmed, F., Otayf, A. Y., Carrascosa, C., Saraiva, A., & Karav, S. (2025). Beyond the Gut: Unveiling Butyrate’s Global Health Impact Through Gut Health and Dysbiosis-Related Conditions: A Narrative Review. Nutrients, 17(8), 1305. https://doi.org/10.3390/nu17081305

Leonid Kim MD (Director). (2025, December 23). Butyrate: Protect Your Brain, Lower Blood Sugar and Fix Leaky Gut [Video recording]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z8Qj2Vc0iNE

Masciadrelli, M. (2023, March 29). Why Are Colorectal Cancer Rates Rising Among Younger Adults? Yale School of Medicine. https://medicine.yale.edu/news-article/with-colorectal-cancer-rates-rising-among-younger-adults-a-yale-cancer-center-expert-explains-there-may-be-more-factors-behind-this-worrisome-trend/

Salsinha, A. S., Araújo-Rodrigues, H., Dias, C., Cima, A., Rodríguez-Alcalá, L. M., Relvas, J. B., & Pintado, M. (2025). Omega-3 and conjugated fatty acids impact on human microbiota modulation using an in vitro fecal fermentation model. Clinical Nutrition, 49, 102–117. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.clnu.2025.04.007

Thumbnail image: Leschelle et al. 2000

_edited.png)

One typical example: food drowsiness, food sleepness, food coma